Study after study has shown that workers are more productive when given the option to work remotely. Yet too many bosses still conflate hours spent in the office with dedication to the job. Many CEOs have said outright that not showing up to the office will hurt your career.

What's an ambitious remote worker to do?

In a perfect world, your work would speak for itself. Your boss would automatically recognize you for going above and beyond and give you a promotion with a nice little raise to boot.

In the real world, people who know how to make themselves and their contributions seen (without being annoying about it) get ahead of their higher-performing peers all the time. As the work world shifts from an hours-worked mentality to a work-accomplished one, remote workers need to master the subtle art of "managing up" and be proactive in making sure their work is seen.

For those of us who find self-promotion intimidating or just plain distasteful, how exactly should we go about demonstrating our value at work — particularly when the impact of our work is often so difficult to measure in the first place?

The metric “black hole”

In Deep Work, author Cal Newport defines a concept he refers to as the metric black hole. In a business environment, if the metrics that determine success for your position are unclear, it’s difficult to figure out where you stand in the organization or know if you’re doing a good job.

They [workers] want to prove that they’re productive members of the team and are earning their keep, but they’re not entirely clear what this goal constitutes. They have no rising h-index or rack of repaired motorcycles to point to as evidence of their worth.

If you’re a motorcycle mechanic, a rack of repaired motorcycles is a clear indicator you can point to after a hard day’s work. Similarly, the h-index is a grading score given to professors at research universities that ranks their impact in a chosen field. Both a high h-index and a rack of repaired motorcycles are easy metrics to point to that demonstrate your value. For the typical knowledge worker, these metrics aren’t easily available.

If you work in a Marketing department, the overall goal might involve growing the company’s client base. That’s how the department is evaluated, but what about your specific role? Depending on the size of the department, it can be hard to tie your actions directly to client growth.

If you’re leading a team, there isn’t a universally-accepted “leadership score”. Much of your day might consist of one-on-one meetings with team members offering mentorship or advice. Sure, you have your team’s performance to point to at the end of the quarter, but what metric or measure can you use to illustrate your specific impact?

Newport goes on to explain that this struggle to come up with a clear demonstration of value in an organization leads to a reliance on shallow vanity metrics.

In the absence of clear indicators of what it means to be productive and valuable in their jobs, many knowledge workers turn back toward an industrial indicator of productivity: doing lots of stuff in a visible manner.

These vanity metrics might include how quickly you respond to an email or Slack DM or how many meetings you’ve attended over the past week. Those things constitute “work”, but they have next to no correlation to how much value you’re building for the company.

So how do you promote yourself and your work?

If relying on vanity metrics isn’t going to demonstrate your value in an organization, what metrics should you rely on? Here are three steps knowledge workers can follow to naturally build and demonstrate value in their organizations (without coming off as arrogant jerks):

Step 1: Understand the difference between intensive and extensive value.

Author Robert Greene has done expansive research around building value within both organizations and individual relationships, drawing on countless examples in history. In The 48 Laws of Power, he provides a helpful distinction between two types of power — intensive and extensive. To illustrate the difference, he contrasts two vastly different yet notably influential individuals — Michelangelo and Henry Kissinger.

Michelangelo’s power was intensive, depending on one skill, his ability as an artist; Kissinger’s was extensive. He got himself involved in so many aspects and departments of the administration that his involvement became a card in his hand.

Intensive value is derived from a specific skill you’ve developed over time. You’re the best developer or designer in the world, for example. Whenever someone has a complex code-related question, you’re the one they come to for advice. You’ve established yourself as the domain expert in a specific part of the business.

Extensive value is derived from your relationships with others. You’re viewed as a connector within an organization. You’re involved in moving multiple related but separate projects along. Team members depend on you to execute on a daily basis in order to keep things running smoothly. Marketing luminary and author Seth Godin calls these kinds of organizational connectors “linchpins”. According to Godin, a linchpin is “the individual in the organization who collects, connects, and nurtures relationships is indispensable.”

Both pathways — intensive and extensive — can lead to great success. However, it’s imperative to understand the difference and determine the path you want to take. Value doesn’t exist in great quantities in the middle (an average developer with mediocre connections, for example). Value explodes at the extremes.

If your goal is to develop intensive value, you want to build clout around a specific area:

- Take classes and read books about the topic.

- Take on extra side projects to tinker and experiment until you know virtually everything there is to know.

- Join conversations within your organization and outside communities.

- Reach out to influential people in your field and build mentorship relationships with them.

- Within your organization, pay specific attention to decisions around your desired area and find ways to demonstrate your expertise.

If your goal is to develop extensive value, relationships are key. Whereas siloing yourself into one area can help for intensive value, extensive value is built through getting involved in multiple areas throughout the organization.

- Build a thorough understanding of each department, how they’re interlinked, and the key projects going on at any one time.

- Take the time to get to know people within your organization. Grab a cup of coffee with them and get to know what their strengths and goals are. What things at work naturally get them the most excited?

- Offer to help colleagues out whenever you can. It’s a natural way to build strong connections at work. (As a bonus, it also happens to be a natural way to be a nice human being.)

- Use your organizational knowledge and network to connect individuals from different departments to move the needle forward.

Your goal is to build a connection web with you at the center.

Step 2: Build your own scorecard.

Once you’ve decided which type of value you’re looking to build, you need to determine how you’re going to track your progress. Many positions come with built-in metrics that can be used to measure impact. If you’re a support professional, you might look at how many emails you have sent in a given day. Similarly, developers might look at number of issues closed. These metrics can work, but they’re rarely sufficient to demonstrate the full value you bring to the table.

First, they’re one-dimensional so they can’t fully encapsulate everything you’re working on. If you work in sales, you could track how many new sales you make on a weekly basis. However, that vanity metric neglects aspects like the size of the deal and the quality of the new client. If you measured your worth solely by new sales per week, you would be incentivized to close smaller deals more frequently, which might not be in the company’s best interest.

Second, they’re often shallow meaning it’s easy to succeed on paper but fail at the deeper goal. For example, if you’re a developer trying to build intensive value, you could focus solely on lines of code written. However, that doesn’t give any weight to the complexity of the code or the type of project you worked on. Writing 1,000 lines of code in a week for the wrong project doesn’t move things forward. It also doesn’t account for the time you spend thinking about the best way to approach the problem, which is likely when you’re creating the most value for the company.

Third, many built-in metrics feel detached from the desired outcome. If you’re a marketing professional, your goal might be to increase leads coming into the top of the funnel. However, it’s tough to tie the impact of your daily work directly to that goal. It might take weeks to move that needle. Measuring yourself against the number of incoming leads then isn’t a helpful way to track progress.

The solution is not to ditch metrics entirely. As Cal Newport alluded to above with the metric black hole, we need a way to measure our value and track our progress. However, we need to be sure we’re using the right metrics.

Enter Kabir Sehgal — military reserve officer, author, Grammy-winning producer, and investment banker. In an interview on the HBR Ideacast podcast, Sehgal explained how he consistently demonstrates his value as an investment banker despite focusing effort on these other side projects. “I think one of the most important things is being able to measure your impact.”

For example, when Sehgal was working in a non-revenue position developing a client satisfaction survey, he would send out a weekly email to his coworkers and managers detailing his weekly productivity (measured by how many client surveys he sent out) and everything else he worked on. In an environment that lacked clear metrics for success (revenue), Sehgal created his own scorecard and held himself accountable by sending it out weekly to colleagues.

You can do the same thing within your organization. At the start of the year or quarter, identify the progress you want to make and how you’re going to measure success. Here are some tips for selecting the right metrics:

- Select metrics that are easy to measure and highly valuable. You should be able to gauge progress from week to week.

- Build a consistent narrative. If you’re changing up the scorecard each week, you’re not creating an easy narrative to follow. Consistency is key. Each week should build on the next.

- Tie your metrics into the larger company picture. What are the top goals of your organization or team and how does what you’re working on move those forward?

Let’s pull this all together using the example of a support professional. As mentioned above, support roles have built-in metrics (how many interactions you’re doing per day). However, let’s build our own scorecard aimed at developing extensive value. We’ll use this alongside the built-in interaction metric.

Goal: Find more ways to delight customers and deliver customer feedback to teams within our organization.

Success metrics:

- Reach out to five customers each week offering to chat with them individually about their experience. Aggregate this feedback for product teams.

- Compile monthly reports of the top bugs surfaced from customers across all of our products.

- Reach out to 30 refunding customers each month. Deliver refund and cancellation feedback to marketing and product teams.

All of these metrics are easy to measure and tied into the larger picture of helping the company succeed. They also involve other departments so we can focus on that extensive value component.

#3: Send regular updates.

At this point, you know the type of value you want to build. You also have metrics you’re going to use to evaluate your progress. Now, you need to find a natural way to communicate your progress to the people who matter.

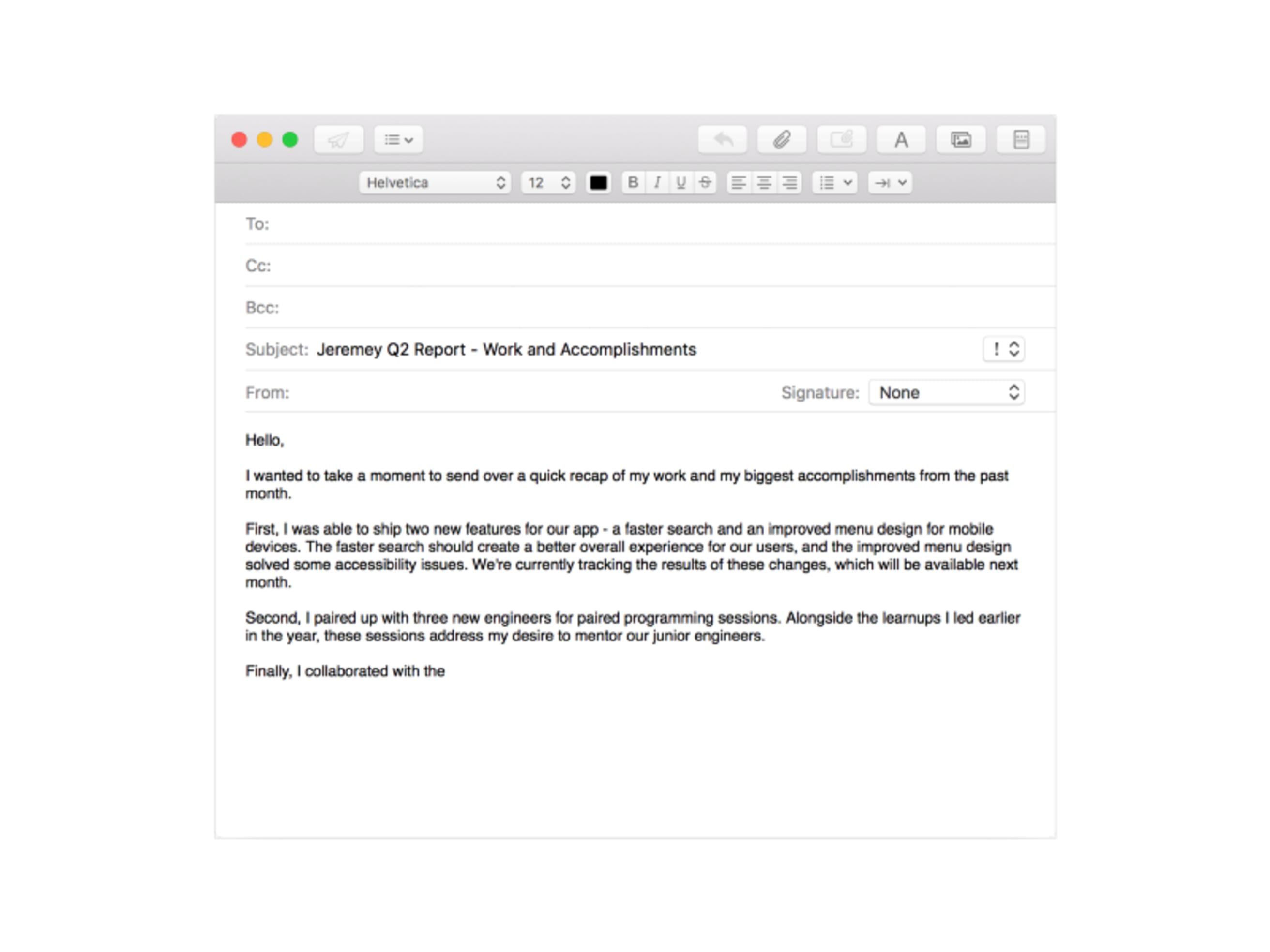

Most individuals wait for a boss or a member of HR to contact them for a performance review. Instead, you can go on the offensive. You already have all of the pieces in place. All that’s left is to share your journey with your team. How you do that will depend on your specific organization. You could send in a quarterly update to HR or send over a weekly email to your supervisor with a recap, or both. The cadence and medium will differ; the goal is still to keep everyone updated with our progress.

What should you include in those updates? This sounds simple, but it’s actually quite tricky. There’s a fine line between demonstrating your value and overly boasting about your accomplishments. This fine line leads many to downplay their contributions in fear of coming across as a braggart.

In an article titled “How to ask for a promotion,” author and entrepreneur Ramit Sethi prescribes an exercise to break the humble nature we use to describe our accomplishments.

List all the ways that you’ve become more valuable to the company…Keep in mind that achievements which seem mundane to you might seem exceptional to someone else. No achievement is too small.

He advises readers to answer specific questions like “Has your communication improved? How so?” and “Do you know the business better? How does this translate to the company’s bottom line?” Sethi created these questions largely to help workers build their case when asking for a promotion, but it can apply beyond those rarer instances too.

Each month, complete your own monthly performance review. Your scorecard should provide the foundation, but you can add in answers to questions similar to those from Sethi:

- What major projects did you move forward in the past month? How does that impact the overall business?

- In what ways did you go above and beyond your normal responsibilities?

- Looking back over your quarterly goals, where did you make progress?

Compile answers to all of these questions along with applicable links to your work. The goal is to keep the review succinct yet detailed (I strive for 250–300 words at most). Send it to your direct supervisor and to Human Resources. Keep a record for yourself to refer back to later.

Sending these recurring updates offers a few benefits:

- If your annual performance review isn’t until December, it’s easy to forget what you worked on in March. This practice ensures nothing falls through the cracks.

- You’ll get better about identifying and communicating your contributions.

- Depending on the size of your organization, it can be difficult to keep track of everyone's work. This helps out your supervisor and Human Resources department by keeping them up-to-date throughout the year and providing a paper trail to fall back on during a performance review.

Don’t leave your remote career up to chance and risk being passed over for a promotion because your boss couldn't see you in the office. Take matters into your own hands by determining the value you want to build, developing your own success metrics, and communicating progress frequently.

This isn’t just about getting promotions and pay raises. Extra money and titles are nice, but ultimately, this is about building a rewarding and meaningful career for yourself, regardless of where you choose to work.

Our professional lives take up a significant portion of our time and play an outsized role in our internal narrative. Following these steps won’t just help you demonstrate your value to others — it will help you develop a concrete vision of what you want to accomplish and ensure that you’re taking the necessary steps to get there. Good luck!