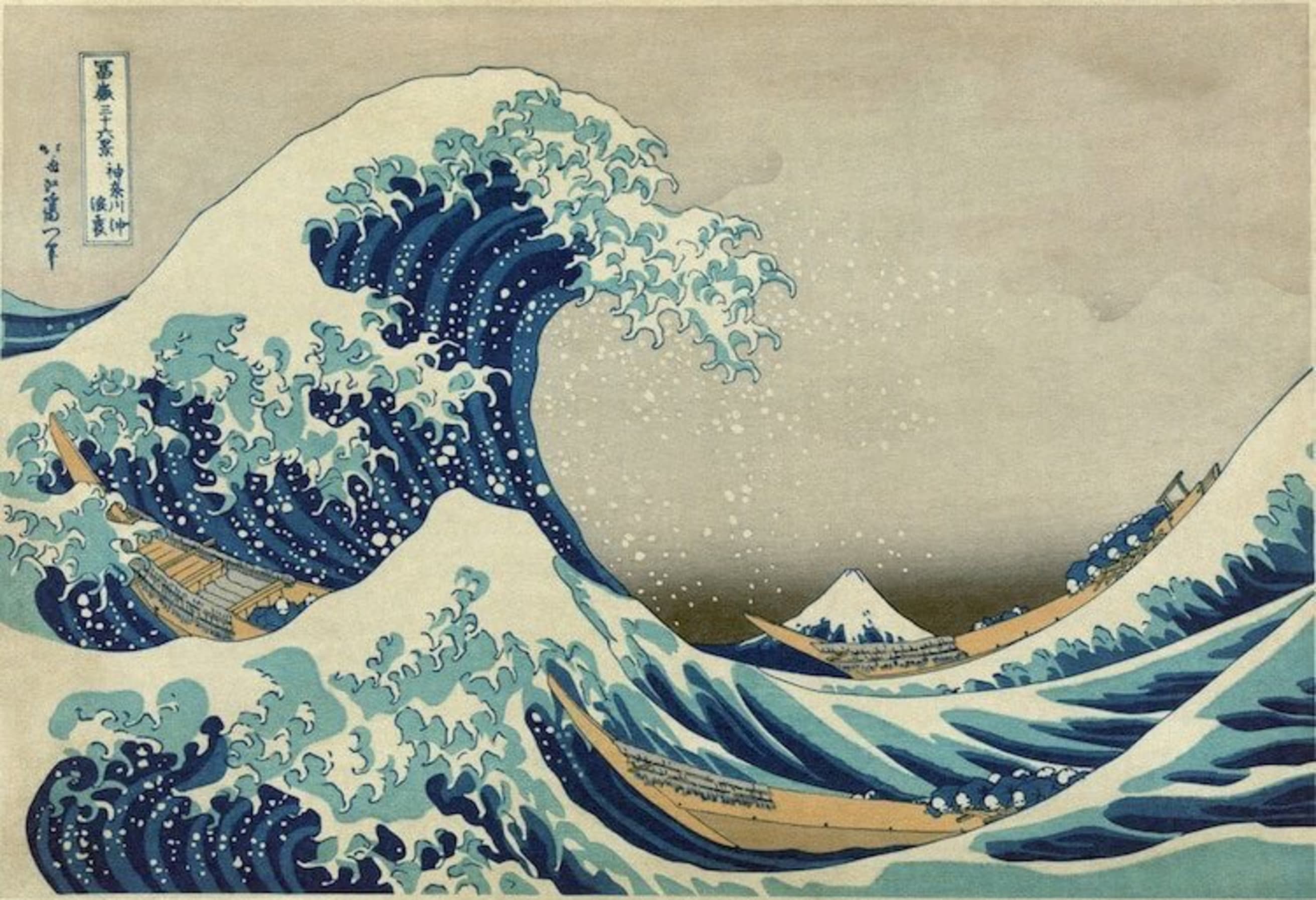

Katsushika Hokusai’s "The Great Wave off Kanagawa" is one of the most recognizable works of Japanese art in the world. Completed in 1831, it’s Hokusai’s most famous work.

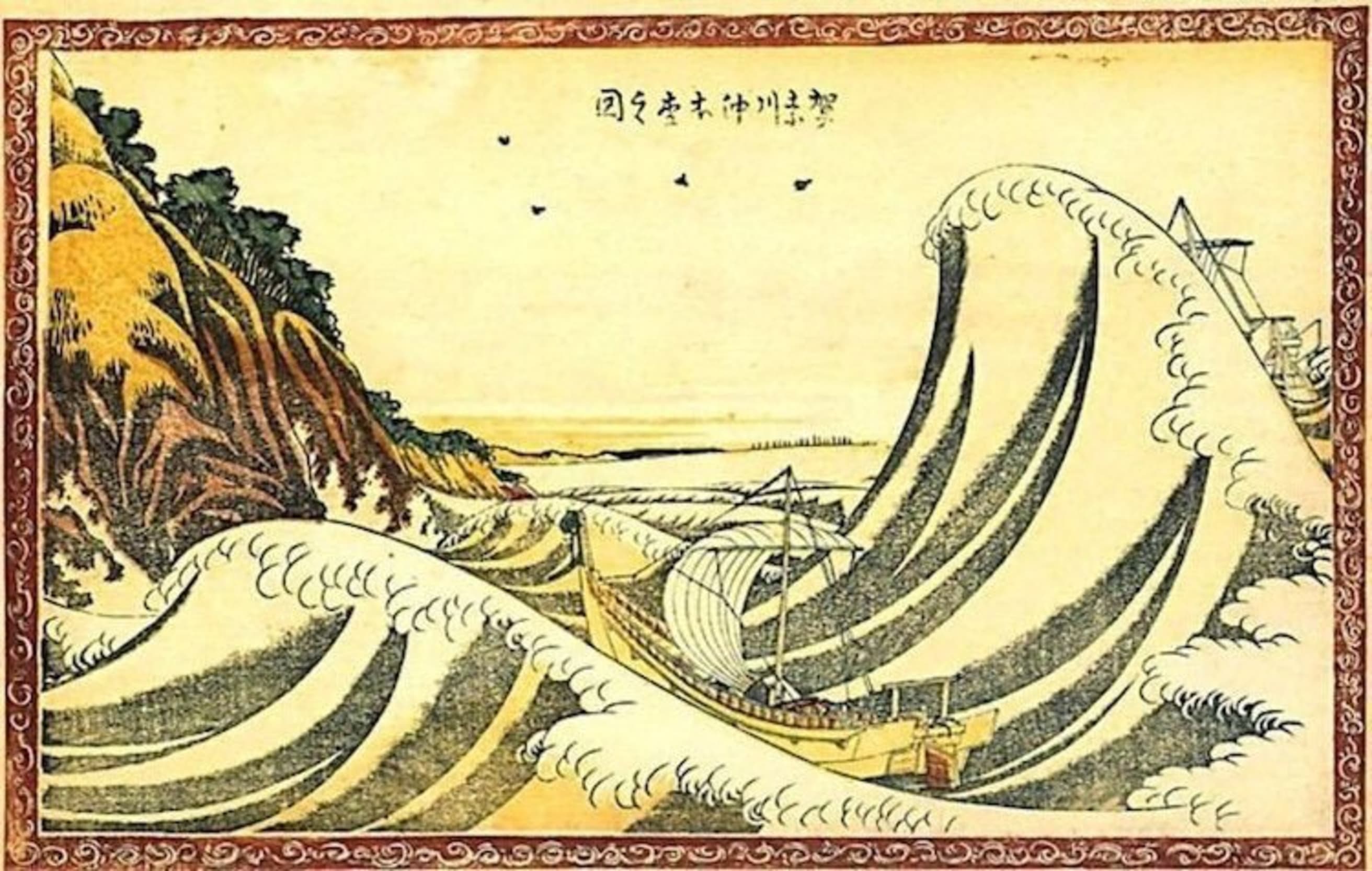

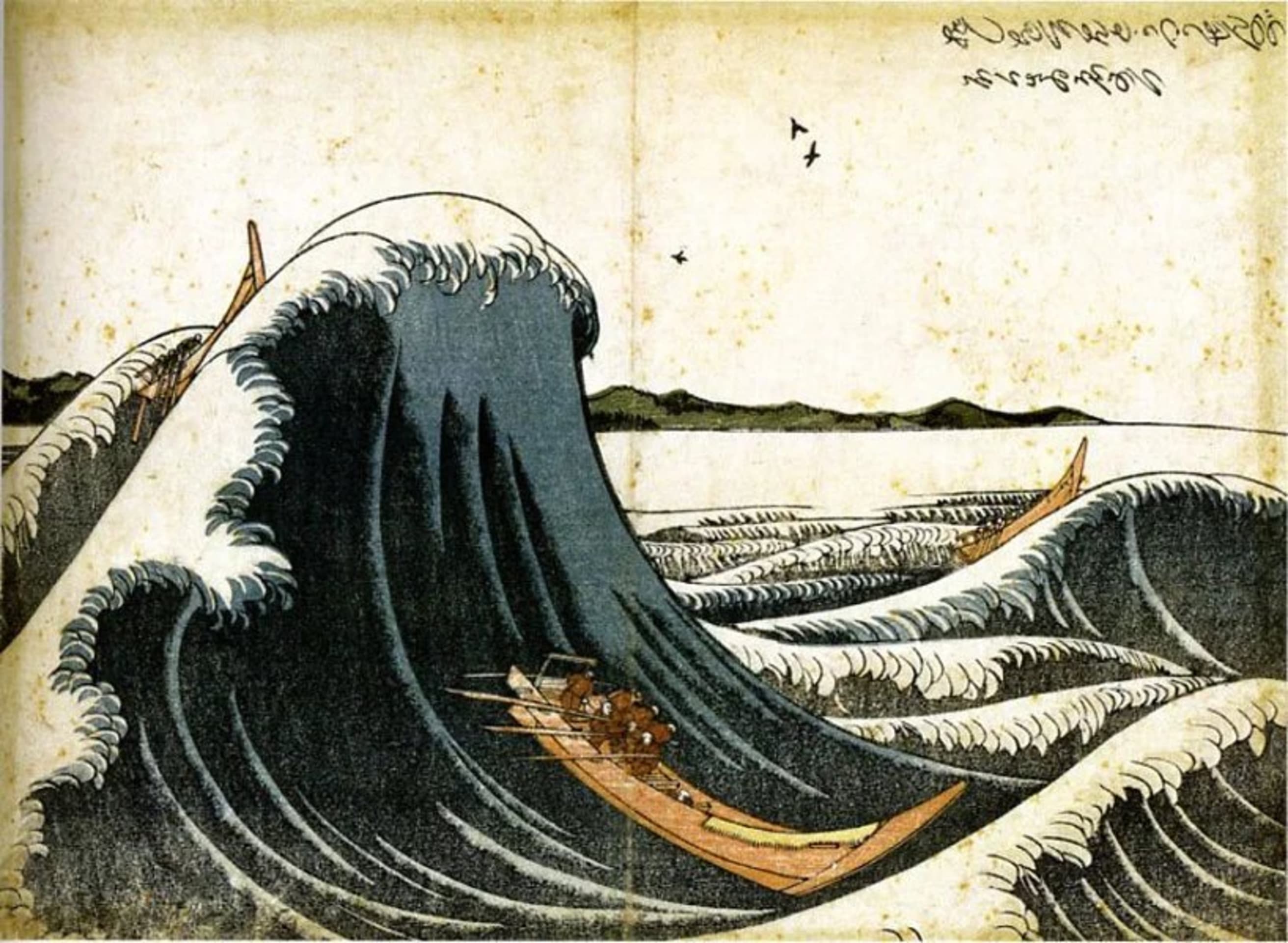

What you might not know is that it took him nearly 30 years to paint it. Hokusai spent decades iterating on his masterpiece, including various attempts at what finally became "The Great Wave."

He was 72 when he finally finished painting his magnum opus.

In following the progression of "The Great Wave," Hokusai’s dedication and increasing control of the medium is evident. Hidden within his famous painting is the same intangible quality shared by all of the world’s greatest achievements in art, music, writing, sports, and technology: mastery.

The path to mastery is available to all of us. With enough effort and persistence, achieving greatness in a chosen field is within reach. We can capture genius and direct our focus and attention to a singular aim that brings both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.

This guide is a deep-dive into understanding mastery and pursuing it for ourselves. It will distill down crucial information you need to walk the path of mastery, bringing together key lessons from works like Robert Greene’s Mastery, George Leonard’s Mastery, Josh Waitzkin's The Art of Learning, and more.

- Robert Greene is an author who has written six best selling books, including the New York Times’ bestsellers The 50th Law and Mastery. Publications like the New York Times, Forbes, and Fast Company have featured his work.

- George Leonard was an author who served as a United States Army Air Corps Pilot and earned a fifth degree black belt in aikido, a Japanese martial art.

- Joshua Waitzkin is a famed chess player who won the U.S. Junior Chess Championship in 1993 and 1994. The film Searching for Bobby Fischer was about his early life. He went on to dominate the field of Tai Chi Chuan, winning several U.S. national medals and a world champion title.

It will include tactical strategies for discovering your call to mastery, staying on its long path, and remaining steadfast in the face of challenges.

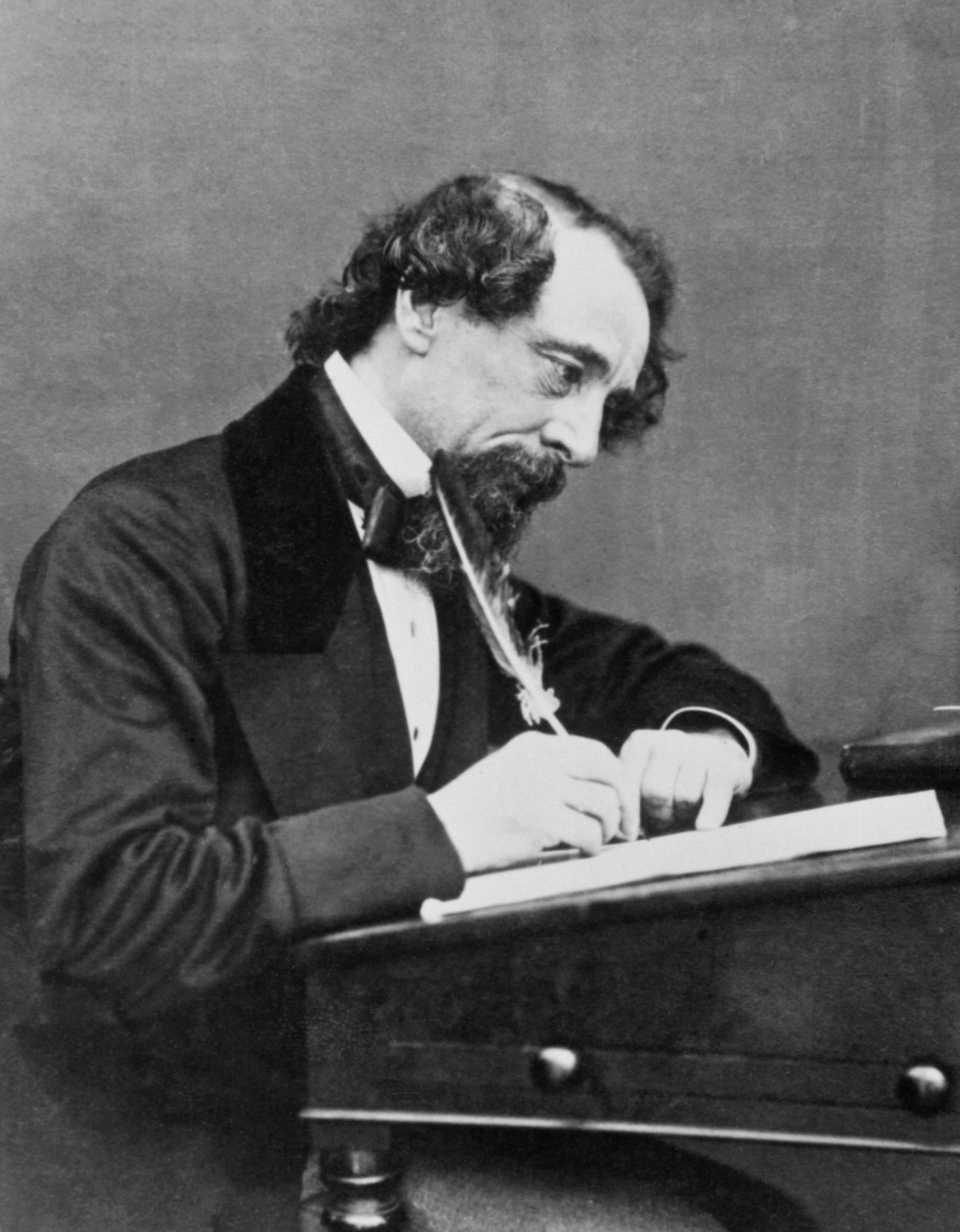

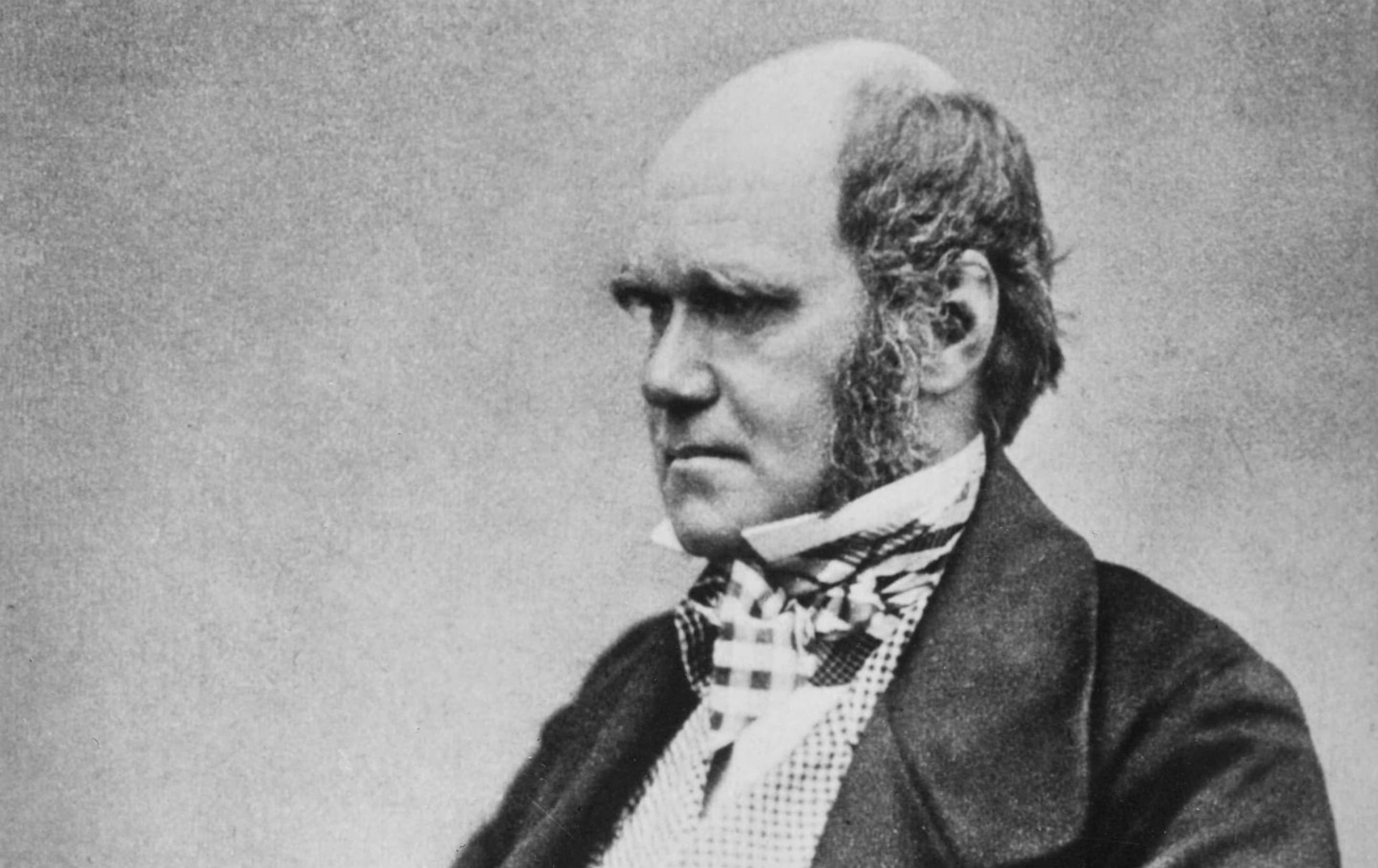

Mastery is not a quick route to fame and fortune. This level of expertise and command can take a decade or more to achieve. You’ll save an immense amount of time and heartache by accepting this: there are no shortcuts on the road to mastery. In studying the path of the masters like Katsushika Hokusai, Charles Darwin, or Maya Angelou, there are no quick hacks to be found. This guide will help you decide if you’re up for the challenge of mastery and embarking on a path of lifelong learning, full of both obstacles and opportunities.

Navigate the Ultimate Guide to Mastery

Understanding Mastery

Find Your Calling

Beginning the Master's Journey

- Lay Your Foundation

- Optimize for Learning Above All Else

- Build a Deliberate Practice

- Find Mentors

- Play Big

- Embrace Failure

Fighting Resistance

Understanding Mastery

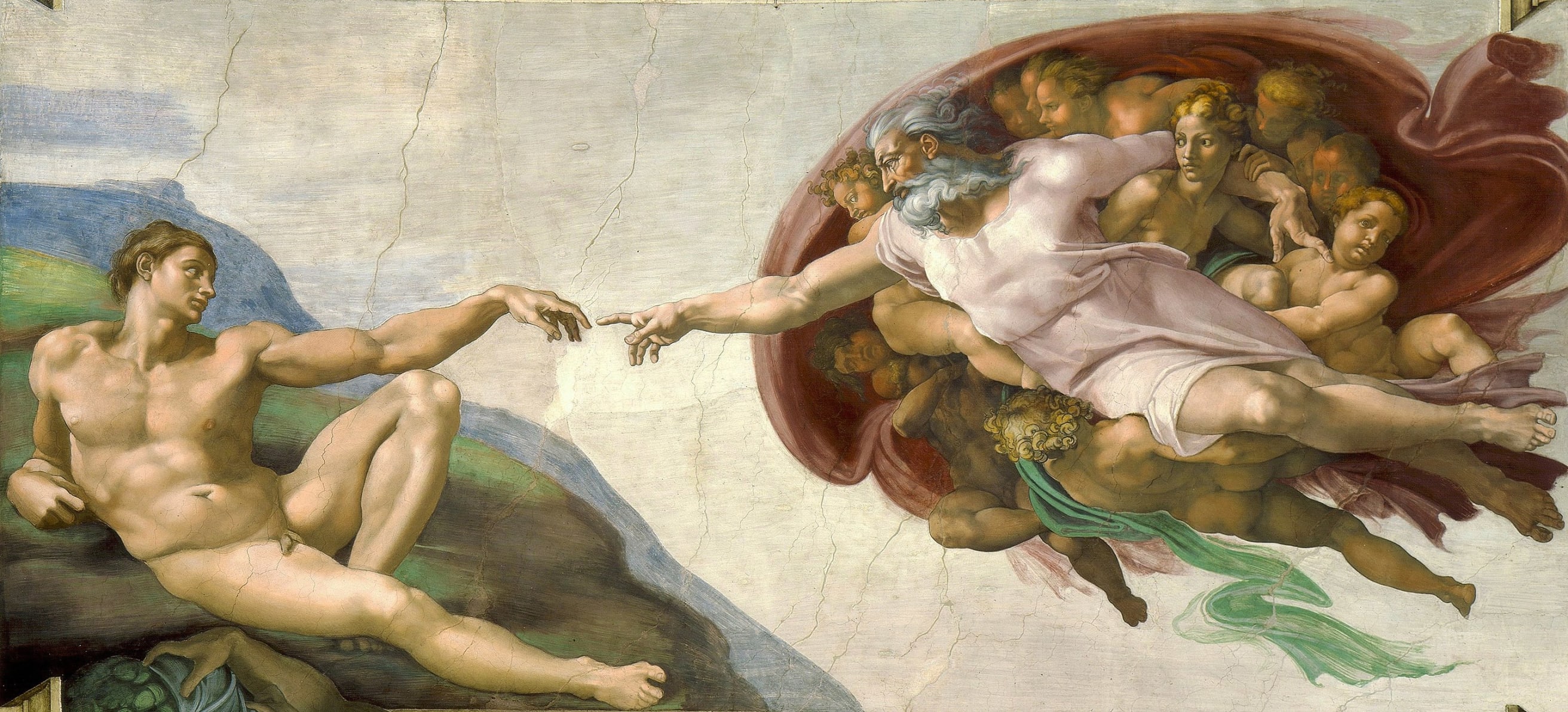

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream. Alex Honnold’s free solo ascent of El Capitan. Simone Biles’s record setting triple-twisting-double-somersault-on-floor spring. We know mastery when we see it.

But how do we define it?

Mastery culminates in these public displays of deftness, but it doesn’t start there. Rather, mastery is the years and decades of learning, practice, failure, and hard-fought improvement that lead individuals toward unmatched greatness.

The Definition of Mastery

Let’s start with what mastery isn’t. It’s not a synonym for genius or giftedness. Those kinds of words suggest that greatness lies beyond our control. That’s not to say that genetics isn't real or important — the proclivities and traits you’re born with are a natural starting point for mastery. A mind that sees the world in abstract shapes and colors may be suited for life as an artist. On the contrary, someone standing 5’7” may need to consider a back-up plan for their NBA aspirations. [See the “Find Your Calling” section for more on choosing your own path to mastery.]

However, mastery requires concerted and long-term effort for which genius or giftedness provide no substitute. In his book, Mastery, Robert Greene makes this distinction clear:

“Mastery is not a function of genius or talent. It is a function of time and intense focus applied to a particular field of knowledge.”

George Leonard, in his book Mastery, provides a definition that emphasizes a process:

“Mastery is not about perfection. It’s about a process, a journey. The master is the one who stays on the path day after day, year after year. The master is the one who is willing to try, and fail, and try again, for as long as he or she lives.”

It’s equally important to understand what mastery feels like. This will vary from field to field. A writer might go into a trance as the thoughts in their head tumble out beautifully onto a page as perfect prose. A seasoned software developer feels the hum of flow as lines of code assemble themselves on a computer screen, solving a complex problem that's eluded them for days.

Greene summarizes the sensation of mastery as “the feeling that we have a greater command of reality, other people, and ourselves.” He adds that a master at work often experiences a “feeling of power”, “exceptional creativity”, and a “sense of control”. Experiencing mastery is turning away from distraction and getting lost in the feeling of sharpening our skills, honing our intuition, and applying our knowledge to our work.

These definitions can shape our expectations and help us understand the key tenets of mastery:

- Mastery is accessible to all of us and distinct from genius and natural-born talent.

- Mastery is not a destination, but a continuous journey in pursuit of excellence.

- Mastery requires focus, commitment, and dedication over a long period of time.

- Mastery is a feeling of heightened control that we can tap into repeatedly.

The Value of Mastery

Recognizing that mastery is not the same as genius is a secret weapon. People who make this mistake see the people they admire as mythical figures. Those who understand that mastery is achieved through hard work see their heroes as future peers.

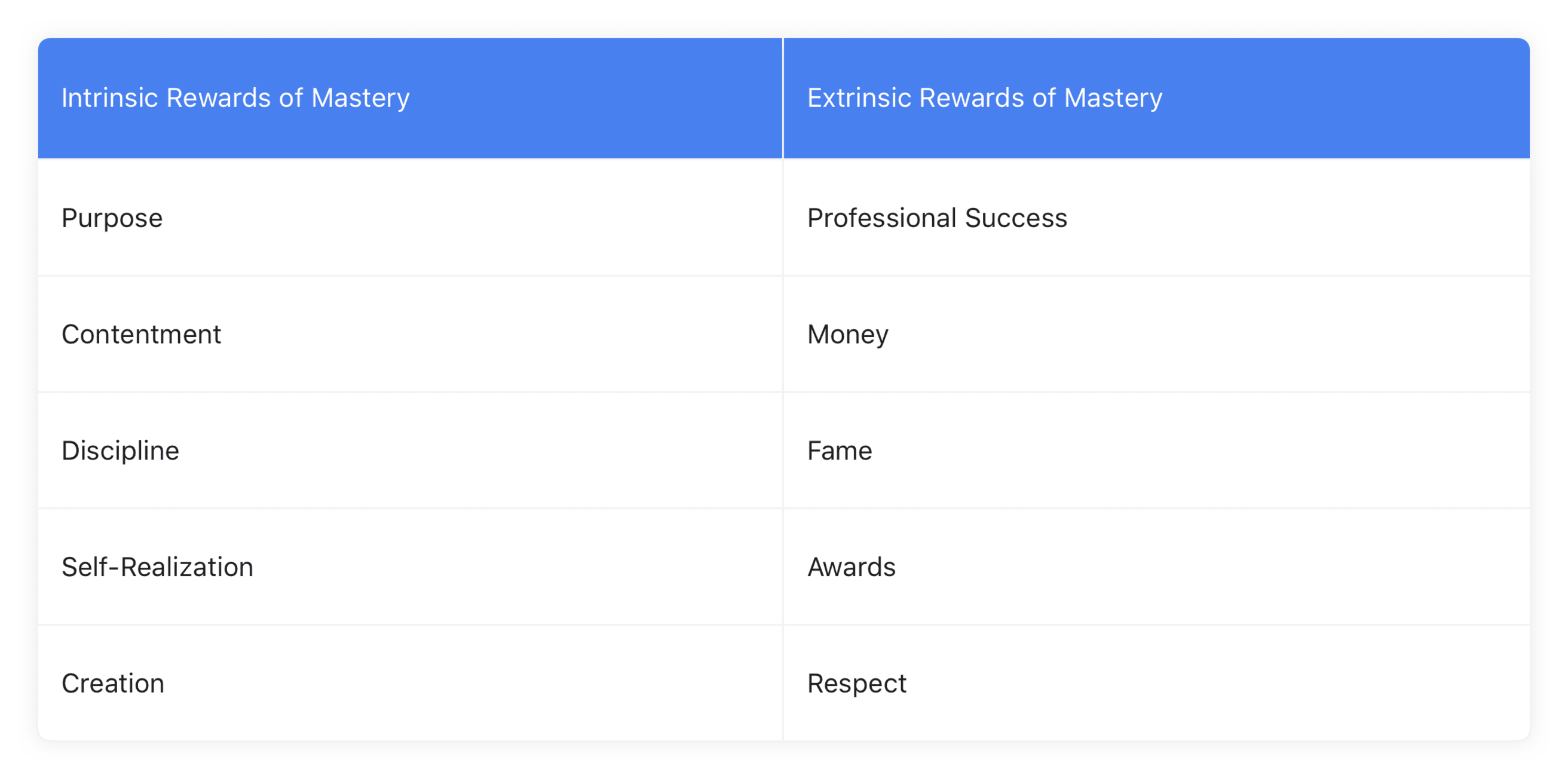

Millions of people count themselves out, forgoing goals within reach. By choosing a different road, the path of mastery, you will stand out from everyone who has settled for mediocrity, and reap the intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.

While mastery often leads to professional success and money, pursuing mastery for those reasons is self-defeating. In the decades-long pursuit of mastery, fantasizing about accolades and adoration won’t sustain you. Though tangible, rewards bestowed by society are often empty and fail to motivate us in the long-run.

Work backwards and choose mastery for mastery’s sake. When your focus is on the mastery of a subject that you feel a genuine connection to, where progression automatically leads to purpose and contentment, you’ll feel compelled to continue and eventually see extrinsic rewards. If you stay the path, you’ll likely work with brilliant people, have enriching conversations, and produce acclaimed work. View these rewards as a byproduct of mastery, not its final form.

As many masters have suggested, the reward of the work itself trumps the ceremony of success. In his book, The Art of Learning, Josh Waitzkin describes the feeling of achieving his goal of becoming a chess master, and beating the record set by famed chess player, Bobby Fischer:

"There was no euphoria, no opening of the heavens. The world was the same as it had been a few days before."

Mastery is its own reward.

The Long Path to Mastery

Mastery, frequently accompanied with fame and acclaim, is often assumed to be the result of overnight success or a lucky break. This is rarely true.

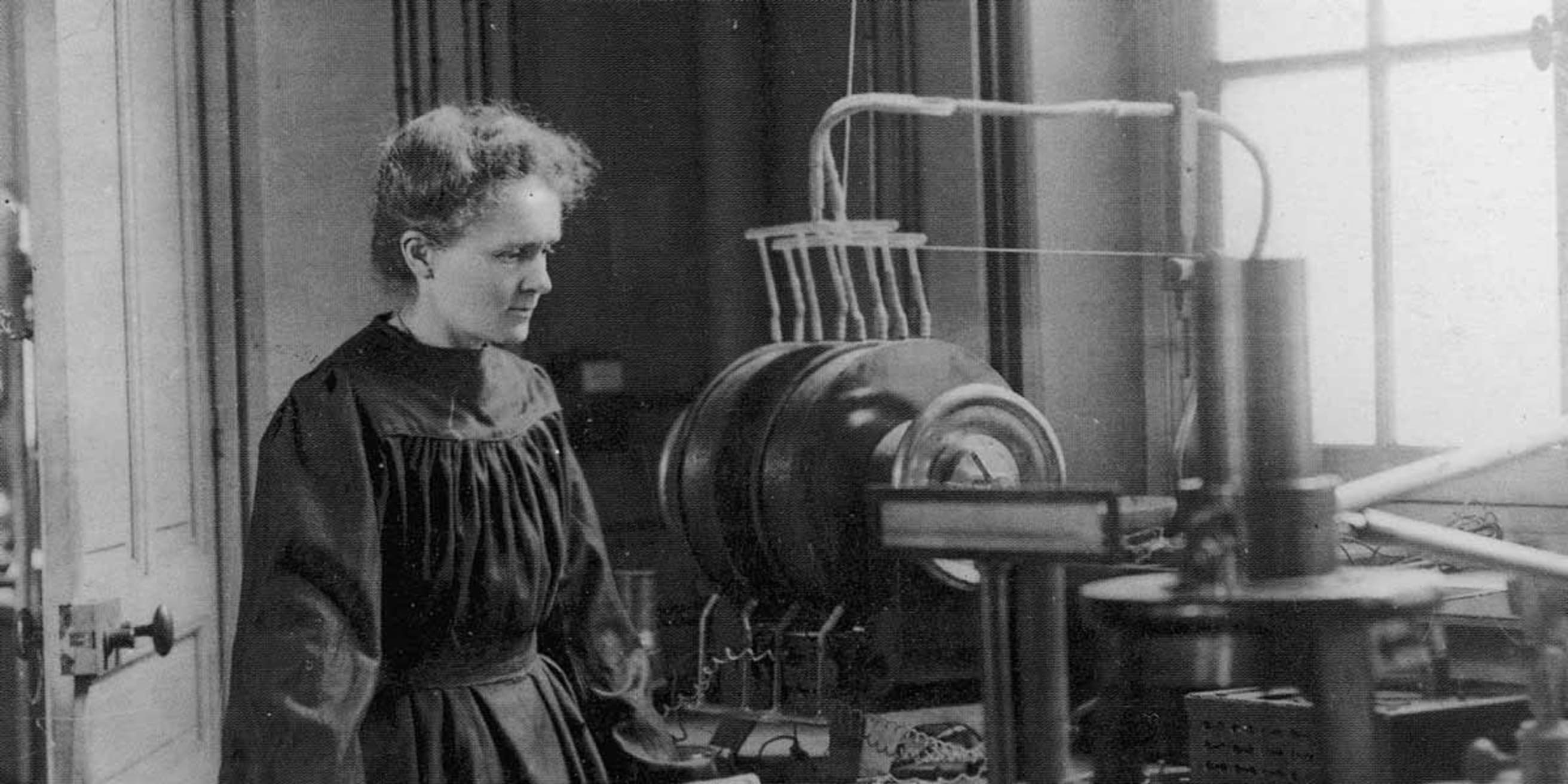

Mastery often means toiling for years in obscurity, learning the basics of your field, and slowly making the transition from novice to master. It’s impossible to start learning the scales on the piano one week and perfectly play Beethoven’s "Piano Sonata No. 32" the next.

Mastery doesn’t happen in two months or twelve. Greene sets expectations for how long mastery can take and the mindset required to endure:

“The road to mastery requires patience. You will have to keep your focus on five or ten years down the road, when you will reap the rewards of your efforts.”

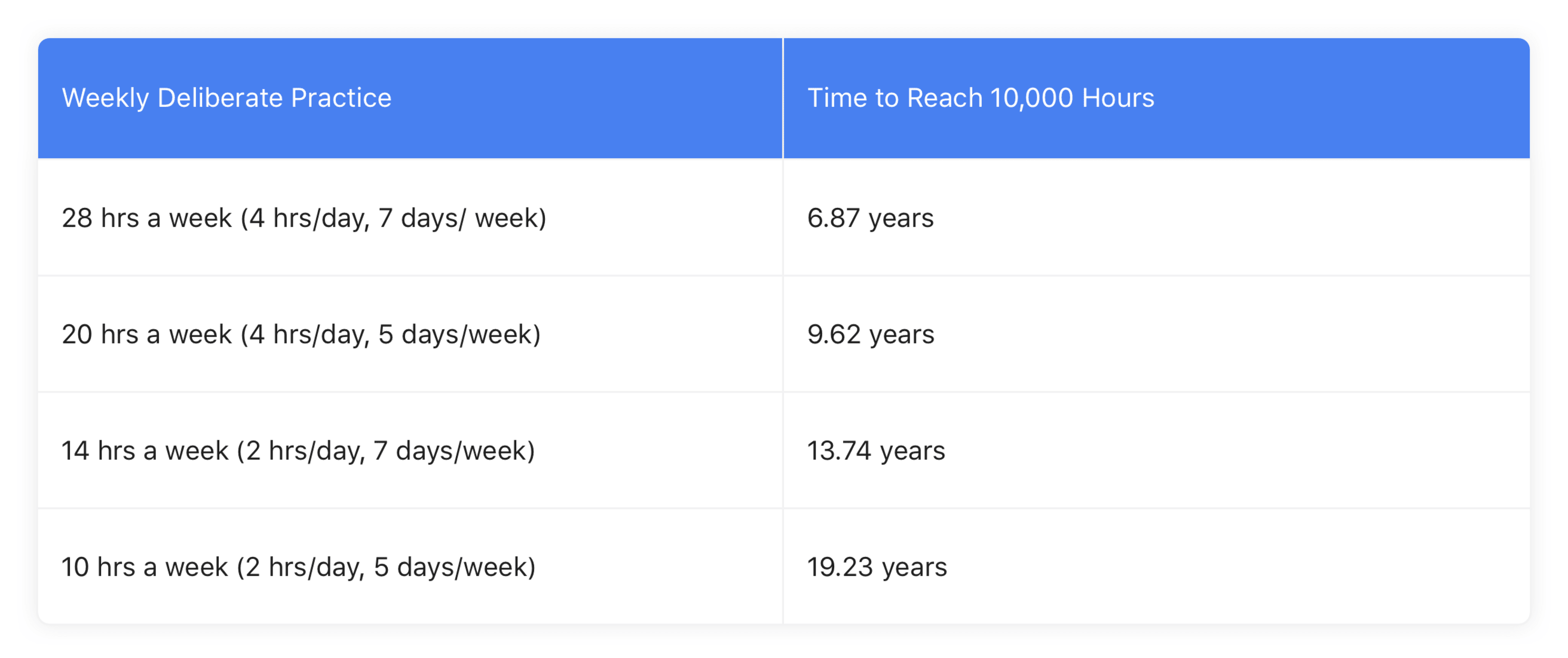

Greene suggests that achieving mastery might take around 10,000 hours. Malcom Gladwell echoes this in his book, Outliers, citing studies and examples of world class performers that indicate 10,000 hours is the “magic number of greatness”. The precise number of hours required to reach mastery is a cause of controversy, and other performance experts have noted that it’s the quality of practice that’s important, not the amount. It’s also important to note that not all hours are equal. Hours 1-100 will be much less effective than hours 8000-8100.

Still, 10,000 provides a helpful benchmark if you ensure those hours are disciplined and focused. It’s also important not to get overwhelmed by the number 10,000 and fail to value the expertise you have gained by 250 hours or 2000 hours.

It’s helpful to envision how long it might take you to reach 10,000 hours given your weekly schedule:

Four hours a day of dedicated practice is often considered an upper bound, after which both mental and physical performance appear to diminish. However, as your skills develop your endurance may follow.

Your hours will vary based on a number of factors:

- Are you pursuing mastery in your full-time job or as a hobby?

- Are you mastering a mental practice or a physical one?

- How much recovery time (mental and/or physical) might you need between sessions?

Be prepared not only for a long path to mastery, but a winding one filled with plateaus and setbacks [See “The Plateau” section]. Ten thousand hours is a non-trivial amount of your life to set towards a singular focus. In the next section, we’ll discuss how to ensure you’re choosing the right path and the most effective tactics for getting the most out of your journey to mastery.

⬆️ Back to the table of contents

Find Your Calling

You’re convinced that mastery is worth pursuing and you’re willing to spend years to achieve your aim. It’s now time to choose precisely what you should master. Greene refers to it as discovering your “Life’s Task”. Leonard describes this as “choosing the master’s journey”.

By embracing your natural inclinations and passions, while ignoring what society suggests will bring you financial security and respect, you can choose your own path to mastery.

Take a Journey Inward

You may already know precisely which skill or area you want to master.

It could be the passion that gnaws at you now, an ever-present distraction from the job you find financially lucrative but unfulfilling. It could be the one that filled your days with delight as a teenager, but that you left behind as an adult, pressured by the burden of being “practical” or “responsible”.

Alternately, your calling could be lurking deep in your mind, waiting to be unlocked by a slew of experiences and some introspection. Regardless, finding your Life’s Task requires a journey inward that often starts by reflecting on your childhood. Greene provides this poignant description of how our dreams may diminish as we move from adolescence to adulthood:

“You possess a kind of inner force that seeks to guide you toward your Life’s Task—what you are meant to accomplish in the time that you have to live. In childhood this force was clear to you. It directed you toward activities and subjects that fit your natural inclinations, that sparked a curiosity that was deep and primal. In the intervening years, the force tends to fade in and out as you listen more to parents and peers, to the daily anxieties that wear away at you. This can be the source of your unhappiness—your lack of connection to who you are and what makes you unique. The first move toward mastery is always inward—learning who you really are and reconnecting with that innate force. Knowing it with clarity, you will find your way to the proper career path and everything else will fall into place.”

Reflecting on what we loved to do as children can be a powerful exercise that brings us closer to the master’s path.

If we come back to the present, it's helpful to consider what feels like play and what feels like work. Paul Graham, a computer scientist, painter, and the Co-Founder of Y-Combinator, describes this heuristic in his essay, “What Doesn’t Seem Like Work?”:

“It seemed curious that the same task could be painful to one person and pleasant to another, but I didn't realize at the time what this imbalance implied, because I wasn't looking for it. I didn't realize how hard it can be to decide what you should work on, and that you sometimes have to figure it out from subtle clues, like a detective solving a case in a mystery novel. So I bet it would help a lot of people to ask themselves about this explicitly. What seems like work to other people that doesn't seem like work to you?”

Here are two basic guidelines for moving towards the path of mastery and choosing the right route:

- Draw on your strengths and natural inclinations. There are probably certain topics and activities you naturally gravitate towards. That might be taking photos or planning events. Follow that thread. You might have a special interest in being in nature. Choose a profession that is conducive to the outdoors, rather than a desk job. If you’re deeply introverted, choose a path that mostly consists of solitary work. If have a highly analytical mind, consider math or software engineering. The thing that people find “weird” about you could be your strongest asset. Greene encourages those who seek mastery to go about, “determining your mental and psychological strengths and working with them”. Mastery is available to many of us, but that doesn’t mean we can master many things. Find your precise zone of genius and move toward it.

- Ignore your weaknesses. Improvement in areas where we’re weak is overrated. Instead, we can partner with people who complement us and outsource or automate what we’re bad at. Focus your energies on where you’re already strong and can truly be the best.

In finding what we want to pursue as our vocation for years to come, these guidelines can light the flame of discovery to the dark and dormant parts of our mind. Consider asking yourself these additional questions too:

- If I quit my job/left school/had no responsibilities tomorrow, what would I choose to do?

- If money was no object, what career would I pursue?

- What do I spend my time on while I’m procrastinating or not working?

- If I could attend university for free, what would I choose to study?

- What parts of my job or life would I be happy to do away with?

- What aspects of my current career path and ambitions are influenced by my friends, family, or society?

- Are my choices driven by a desire for money and titles?

- What can I be the best at?

Once you’ve narrowed down an area or two of interest, ask even more questions:

- Do I have a strong, even obsessive, pull towards x area?

- Can I see myself spending the next 10 years focused on x skill?

- How would I feel if I could jump onto this path today?

It may be the first time in years that you’ve stopped to ask yourself these kinds of questions. Answer as honestly as possible, reflecting on “what is” rather than “what ought to be”. Your answers will guide you in the right direction if you listen closely and are willing to take a calculated risk.

When you finally find the path to mastery you want to take, you’ll know it. Greene describes the feeling of knowing you’ve found your Life’s Path:

“You will recognize it when you find it because it will spark that childlike sense of wonder and excitement; it will feel right.”

Explore Widely

There are more masters than ever in human history. There are fields we can explore that didn’t exist just a decade ago. Many emerging areas lack traditional gatekeepers, making entry and mastery feasible. The rise of e-sports has given rise to professional gamers. Blogging and self-publishing gives anyone with enough interesting things to say a platform to say them.

Mastery necessitates diving deep into the Mariana Trench of a subject. However, at first, it’s wise to go wide. Exploring your inclinations as a child is an important exercise. But with the rapid rate of progress, there are countless new professions that have emerged since you were a kid.

Be strategic in exploring new fields, using your own curiosities and strengths as a starting point.

- Research emerging fields. Find the fields that are just taking shape. Look to fast-growing companies, and review the positions they’re hiring for. Measure your own skills and interests against these roles and consider if it’s a path worth pursuing.

- Socialize and network extensively. Extend yourself beyond your current social circle, and seek out people who have different professions and interests. Attend networking events, ask people for introductions, and generally try to meet as many people as possible. People are often willing to help and answer questions if you express curiosity in their work and what they do. You’ll learn about new fields and may discover information about the right path to embark on.

- Consider formal education. Earning an undergraduate college degree or simply taking a few undergraduate courses can be a broad introduction to a variety of fields. If you’re searching for an emerging field, this may not be the ideal location — academia can often lag behind. However, if you want access to primers on an assortment of fields — software engineering, mathematics, art and design, and more — attending college can be helpful in getting a broad overview of different fields and narrowing down. University can also be a strong venue for meeting future collaborators and discovering future mentors [See the section on “Mentors”].

Turn over a few stones and see what’s under them before settling in for the work that lies ahead.

Narrow Your Niche

Fields are broad. Masters have often found a specific niche within a field that allows them to apply a precise combination of different skills and interests. Greene describes the benefits of finding your niche:

“In either direction, you have found a niche that is not crowded with competitors. You have freedom to roam, to pursue particular questions that interest you. You set your own agenda and command the resources available to this niche. Unburdened by overwhelming competition and politicking, you have time and space to bring to flower your Life’s Task.”

Most musicians master a single genre or play one instrument. Not many authors successfully master writing both fiction and non-fiction. As you go down the path of mastery, refine your skill set and get comfortable with a narrow focus.

Find a path to mastery that allows you to both pursue your interests and stand out. However, discovering your path is only step one. Now, the real trek begins.

⬆️ Back to the table of contents

Beginning the Master's Journey

Mastery can take decades or even a lifetime. It’s impossible to say how years will unfold — who you’ll meet, the opportunities that arise, the serendipitous events that might take you to places you never imagined. Regardless of what takes place, a commitment to mastery means continuously coming back, even in the face of failure.

Committing to deliberate practice and following the tactics of the masters that came before you will help you achieve your own success.

Lay Your Foundation

You can’t become a master without observing the greats that preceded you. Watch your contemporaries closely, but pay even closer attention to your historical counterparts.

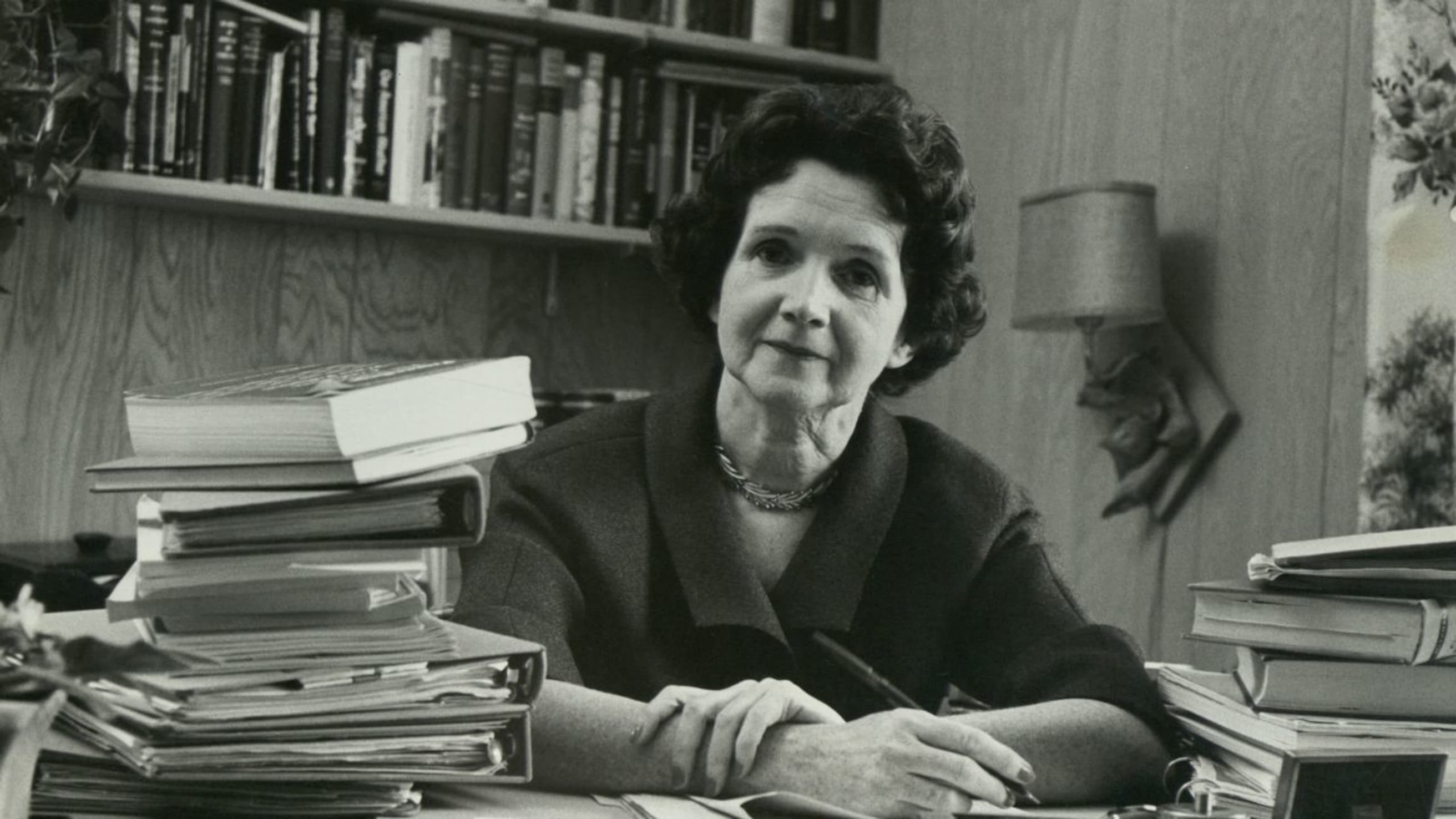

If you want to go into advertising, study David Ogilvy. If you want to study design, ingest the work of Dieter Rams. To understand nature writing, read Rachel Carson. Build a foundation of knowledge that includes the classics of your field.

Craft a syllabus of your intended field of mastery. Ensure it includes the fundamental and defining works of your field. Learn the players and understand the great contributions to your area of study.

When Josh Waitzkin halted his competitive chess career and sought to master a martial art, he had to start another mastery path from scratch. He began with the classics:

“First things first—I had to begin with an understanding of the art’s foundation. The martial philosophy behind Push Hands, in the language of the Tai Chi Classics, is ‘to defeat a thousand pounds with four ounces.’ Chen’s barely perceptible contact between his wrist and my pushing hand was an embodiment of the “four ounces,” but there are countless manifestations of this principle inside and outside of Tai Chi—some physical, some psychological.”

By studying your field of choice, you’ll begin to make connections. Keep a record of what you’ve read, and take notes to internalize what you’ve learned.

Your syllabus should be bottomless. Always add more to it. One insightful book may reference another that you need to devour. An artist who inspires you may cite their influences, leading you down another rabbit hole.

Focus on primary sources, but make time for secondary sources that shed light on how people analyze and synthesize the work in your field. Learn the common rookie mistakes of your area of focus so you don’t make them too.

Optimize for Learning Above All Else

Choose to learn at every opportunity. Greene describes the importance of this mindset on the path to mastery:

“...value learning above everything else. This will lead you to all of the right choices. You will opt for the situation that will give you the most opportunities to learn, particularly with hands-on work.”

Here are a few different areas where you can optimize for learning:

- Your job. While money and learning can often collide, sometimes the path most suited to learning isn’t the most lucrative — a low paying job at a startup, an unpaid internship, or an opportunity to job shadow a mentor. If you’re privileged enough — or hungry enough — to take on these opportunities, they may be worthwhile. If you have aspirations to climb the academic ladder, the ascent can often be financially difficult, with low paid assistantships or post-doctoral positions. Having studied and gained an understanding of your field, you’ll know where the most crucial opportunities for growth lie. Run towards them.

- Your acquaintances. As the saying goes, you’re the average of the five people you spend the most time with. Seek out people you can learn from. Welcome the opportunity of being the dumbest person in your circle of acquaintances.

- Your attitude. Let go of pride. Rapid learning often means asking stupid questions or making a fool of yourself. Post a cover of a song you’ve recorded to YouTube for feedback. Cold message someone you admire and ask them the question you’ve been contemplating. Don’t be afraid to say, “I still don’t get it,'' after having something explained to you for the second time. By cultivating an attitude that’s unafraid of negative feedback or failure, you’ll fly past your peers and earn the rewards that come with bravery.

By taking the learner’s path, you’ll avoid plateaus and dive deeper into the complexities of your field.

Build a Deliberate Practice

To command an audience on stage, you’ll need to practice your ability to tell a compelling story. To defeat your opponent in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, you’ll have to put in your hours on the floor mat. Deliberate practice is the foundation of mastery. Leonard George describes this succinctly:

“Ultimately, practice is the path of mastery. If you stay on it long enough, you’ll find it to be a vivid place, with its ups and downs, its challenges and comforts, its surprises, disappointments, and unconditional joys. You’ll take your share of bumps and bruises while traveling — bruises of the ego as well as of the body, mind, and spirit — but it might well turn out to be the most reliable thing in your life.”

Deliberate practice should be a part of your regular routine. Set a schedule that allows you to accumulate those 10,000 hours over the years during work hours, in your free time or both. Heed Greene’s advice on making your deliberate practice valuable:

“The key, then, to attaining this higher level of intelligence is to make our years of study qualitatively rich. We don’t simply absorb information — we internalize it and make it our own by finding some way to put this knowledge to practical use.”

If you’re learning front-end development, don’t just run through sample problems online, practice repeatedly by creating real websites. If you’re working on painting portraits that fail to look lifelike, narrow your focus and practice drawing only the eyes until you’ve captured an increasingly human twinkle. Deliberate practice is focused and forces you to direct your attention, again and again, towards improving your weaknesses.

Set a consistent routine. Mastery isn’t accidental. You need to develop purposeful habits that hone your skills. While the importance of a strict routine is obvious if you’re pursuing mastery alongside a different full-time occupation, it shouldn’t be understated if you plan to achieve some of your deliberate practice at work. For example, a young physicist may want to spend their days on research and problem-solving, only to have their calendar bombarded by the administrative demands and meetings of their university’s faculty.

By making constant and non-negotiable space in your schedule for deliberate practice, you can continue along the path of mastery even when other priorities arise.

Embrace boredom. Deliberate practice will lead to breakthroughs that make the journey worthwhile. But, for the most part, progress will feel painfully slow. Greene encourages us to embrace the slog:

“Second, the initial stages of learning a skill invariably involve tedium. Yet rather than avoiding this inevitable tedium, you must accept and embrace it. The pain and boredom we experience in the initial stage of learning a skill toughens our minds, much like physical exercise. Too many people believe that everything must be pleasurable in life, which makes them constantly search for distractions and short-circuits the learning process.”

Prioritize deep work and flow states. Deliberate practice is necessarily focused. It can’t be completed while distracted. Prioritize long sessions of deep work, and embrace the feeling of flow. Get lost in the heightened focus and adrenaline that comes from sparring with an opponent in the ring, producing the melody for a song, or training for a triathlon.

Don’t use kid gloves. There’s comfort in practicing what we’re good at, like using the same narrative arc while writing a short story or studying the scientific theories we’re already familiar with. It’s only when we expose ourselves to the uncomfortable sensation of feeling stupid or incompetent that we grow.

Greene emphasizes the importance of toughness on oneself to ascend to new heights of mastery, eliminate your weaknesses, and surpass your peers:

“...go in the opposite direction of all of your natural tendencies when it comes to practice. First, you resist the temptation to be nice to yourself. You become your own worst critic; you see your work as if through the eyes of others. You recognize your weaknesses, precisely the elements you are not good at. Those are the aspects you give precedence to in your practice...You invent exercises that work upon your weaknesses. You give yourself arbitrary deadlines to meet certain standards, constantly pushing yourself past perceived limits. In this way you develop your own standards for excellence, generally higher than those of others.”

Perform self-assessments. Something that separates amateurs from masters is their insistence on regular self-assessment. An amateur shies away from assessing their own work, failing to critique it or compare it to the work of their peers or masters in their field. Someone on the path to mastery seeks opportunities to improve and correct their work or performance through self critique. While training for the biggest Tai Chi competition of his life, Waitzkin took a decidedly different approach:

“I recorded all of Dan’s and my training sessions. Then, every night I would go home and study the tapes.”

Similarly, Greene encourages those pursuing their Life’s Task to find the distance to assess themselves as objectively as possible:

“Once an action becomes automatic, you now have the mental space to observe yourself as you practice. You must use this distance to take note of your weaknesses or flaws that need correction—to analyze yourself.”

Building a deliberate practice that’s consistent, focused, and challenging puts the path of mastery within reach.

Find Mentors

Many great masters had mentors. Maya Angelou had Bertha Flowers. Michelangelo had Lorenzo dé Medici.

Greene describes the immense value a mentor can bring to mastery:

“Mentors do not give you a shortcut, but they streamline the process. They invariably had their own great mentors, giving them a richer and deeper knowledge of their field. Their ensuing years of experience taught them invaluable lessons and strategies for learning. Their knowledge and experience become yours; they can direct you away from unnecessary side paths or errors.”

Finding your own mentor is challenging. The masters of your field are often busy and inundated with requests for mentorship. It’s important to stand out from your peers as someone who can provide value in your mentor-mentee relationship too. Greene suggests volunteering your time for their benefit as a strategy for wooing a potential mentor:

“If you can demonstrate the ability to help them organize themselves on these fronts to a degree that others cannot, it will be much easier to get their attention and interest them in the relationship. Do not shy away from anything menial or secretarial. You want person-to-person access, however you can get it.”

Unfortunately, you can’t always acquire a mentor. In these cases, though not ideal, turn to other sources for expertise: peer groups, books, podcasts, Twitter. Often the people whose skills you want to acquire are a click away, sharing their thoughts in an interview or tweeting about the early failures they faced in their career. This can give you an up-close view of their thought process and how they work. Learning by observation, through a slew of virtual mentors, can be a temporary substitute for a real mentor. However, most performance experts say real-life mentorship is the gold standard. Leonard echoes this sentiment:

“Instruction comes in many forms. For mastering most skills, there’s nothing better than being in the hands of a master teacher, either one-to-one or in a small group. But there are also books, films, tapes, computer learning programs, computerized simulators (flight simulators, for example), group instruction, the classroom, knowledgeable friends, counselors, business associates, even “the street.” Still, the individual teacher or coach can serve as a standard for all forms of instruction, the first and brightest beacon on the journey of mastery.”

Your mentor can help you along the path of mastery, having embarked on the same one themselves. However, at a certain point your mentor-mentee relationship will make a shift. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, your goal should eventually be to surpass your mentor. Many historical examples of mentor-mentee relationships have resulted in eventual jealousy and discontentment. Your aim should be to avoid this and instead become peers, egos unbruised. In all, the best mentorship relationships can supercharge your growth and accelerate your learning.

Play Big

After years of practicing Push Hands Tai Chi, Waitzkin was a decorated national champion in the United States. He had no concept of what awaited him when he moved to compete internationally in Taiwan. Waitzkin lost his first match there and resolved to come back and win it all. He eventually secured a victory. But his initial mistake was in underestimating his opponent:

“Until I went to Taiwan, I had no idea what to expect. And sure enough, the top competitors were armed with a skill set I had never dreamed of.”

“The skill level in U.S. Push Hands events, including our championships, doesn’t compare to such competitions in Taiwan, where Push Hands is the national sport. Mediocrity can be self-nurturing, and frankly, many U.S. Push Hands players delude themselves about their level of proficiency.”

Achieving mastery necessarily means we have to rise to the level of other masters. To achieve mastery, it’s better to be a small fish in a big pond than a big fish in a small pond. The former will challenge us and force us to rise to the occasion. The latter will leave us complacent with no real way to improve.

Meet the masters of your field on their home court. If you want to be a prolific filmmaker, move to Los Angeles. If you want to study artificial intelligence, Silicon Valley remains the largest tech hub in the world.

If you’re a competitor, seek out increasingly more challenging opponents, as Waitzkin did on his journey to secure an international title:

“A competitor needs to be process-oriented, always looking for stronger opponents to spur growth, but it is also important to keep on winning enough to maintain confidence.”

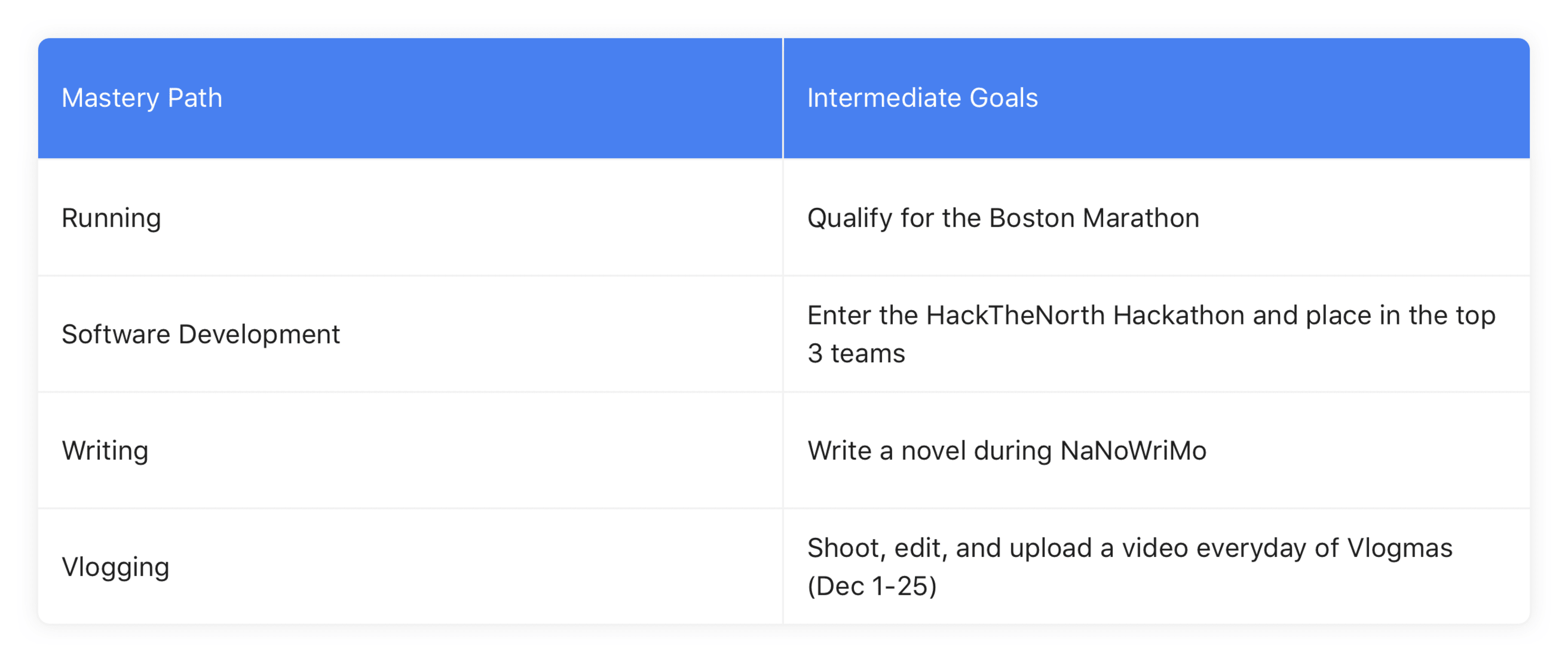

While mastery remains a journey rather than a destination, setting goals and milestones can spur your progress forward. Leonard, explains this seeming contradiction:

“The journey of mastery is ultimately goalless; you take the journey for the sake of the journey itself. But, as I’ve pointed out, there are interim goals along the way, the first of which is simply starting the journey. And there’s nothing quite so immediately energizing on any journey as the intermediate goal of a tough, firm deadline—as is well known to anyone who has faced an opening-night curtain, a business-deal closing date, or a definite press time for an article or book.”

There’s no shortage of goals you set for yourself as you continue along the path of mastery, whatever that may be.

Playing big, by concentrating in areas of expertise, competing against strong opponents, and setting ambitious goals, are all strategies to move along the path of mastery.

Embrace Failure

Playing with amateurs is comfortable as you rack up win after win. Conversely, exposing yourself to the best in the world means you’ll often be bested by your opponents.

A senior peer you admire may bring up a key error you’ve made, leaving you embarrassed. On the path to mastery, get comfortable with this feeling of failure.

Instead of fearing it, move towards it. We learn more of our life lessons from failure, not success. Failures cement what we did wrong in our brains, a permanent mark on our minds that reminds us to do better. With enough practice, the biting shame and anger of failure dissipates as you recognize the worst case scenario simply isn't that bad. In fact, without failure, you would be unable to ascend to new levels.

Greene describes this willingness to put ourselves out there as the “Experimentation” or “The Active Mode”. He suggests the following:

“Expose your work to the public for active feedback. If you wait until you're ready, you'll never be ready.”

He adds:

“Often you must force yourself to initiate such actions or experiments before you think you are ready.”

This was a key tenet of Waitzkin’s journey to becoming a skilled martial artist:

“I spent many months getting smashed around by [his rival] Evan, and admittedly it was not easy to invest in loss when I was being pummeled against walls—literally, the plaster was falling off in the corner of the school into which Evan invited me every night.”

Evan, was unwilling to do the same:

“Most critically, Evan was unwilling to invest in loss himself. He could have taken my improvement as a chance to raise his game, but instead he opted out.”

Failure is uncomfortable and makes us feel weak and powerless. It brings us back to feeling like a novice, erasing all the hard work we’ve done. If you’re one of the few people who can chase failure and make it an integral part of your mastery plan, you’ll be in a league of your own.

⬆️ Back to the table of contents

Fighting Resistance

On any important pursuit, obstacles will arise. Mastery is no different. In Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art, he describes the force that derails our plans and sabotages our dreams — Resistance:

“To yield to Resistance deforms our spirit. It stunts us and makes us less than we are and were born to be.” He also adds, “Resistance will tell you anything to keep you from doing your work. It will perjure, fabricate, falsify; seduce, bully, cajole. Resistance is protean. It will assume any form, if that's what it takes to deceive you.”

Our greatest power over resistance is knowing of its existence and the many forms it can take: complacency, stagnation, distraction, emotional turmoil, rejection, and burnout. Know the shapes resistance can take to derail your journey, so you're better prepared for its attempts to obstruct your path to mastery. Leonard cites the same phenomenon:

“Expect resistance and backlash. Realize that when the alarm bells start ringing, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re sick or crazy or lazy or that you’ve made a bad decision in embarking on the journey of mastery. In fact, you might take these signals as an indication that your life is definitely changing—just what you’ve wanted.”

This section will detail the various setbacks that can lead us astray from our chosen path and pull us away from mastery.

Master Your Emotions

Mastering your own emotions is the skill on which every true pursuit of mastery is built. Without a foundation of mental resilience, the practice of mastery is built on shaky ground and often comes tumbling to the ground. Mastery requires immense patience — you won’t see excellence if you constantly give up. Ascending fields often means working closely with collaborators. You’ll curtail your success if you can’t effectively work well with others.

Greene describes the importance of emotional control on the road to mastery:

“Understand: to create a meaningful work of art or to make a discovery or invention requires great discipline, self-control, and emotional stability. It requires mastering the forms of your field.”

Waitzen echoes this sentiment:

“Mental resilience is arguably the most critical trait of a world-class performer, and it should be nurtured continuously.”

Consider these strategies for building mental resilience:

- Practice mindfulness meditation. Meditating helps quiet your mind, both while you’re mediating and when you’re not. Mindfulness is a tool you can reach for over and over again to cultivate mental calm and equanimity.

- Practice negative visualization. Steel yourself against “the worst thing that could happen” by practicing negative visualization — a stoic practice that asks you to contemplate your life at its worst.

Ignore Distraction

The distractions of everyday work and life have a way of whittling hours from the little time you do have. Waitzkin bemoans a culture that emphasizes distraction over focus:

“Our obstacle is that we live in an attention-deficit culture. We are bombarded with more and more information on television, radio, cell phones, video games, the Internet. The constant supply of stimulus has the potential to turn us into addicts, always hungering for something new and prefabricated to keep us entertained.”

Unless your path to mastery includes television writing or production, game development, or adjacent careers in technology and entertainment, it’s likely you spend too much time online. Mastery necessitates deep work and focus that can’t occur if you’re distracted, constantly checking your phone and social media.

But distraction is much broader than digital disturbances. Often we use other distractions as a form of procrastination: workplace drama, demands on our time, or shortcuts that promise a fast path to where we want to go.

By maintaining a singular focus, we can be more equipped to handle distractions. Here are a few strategies to combat them head-on:

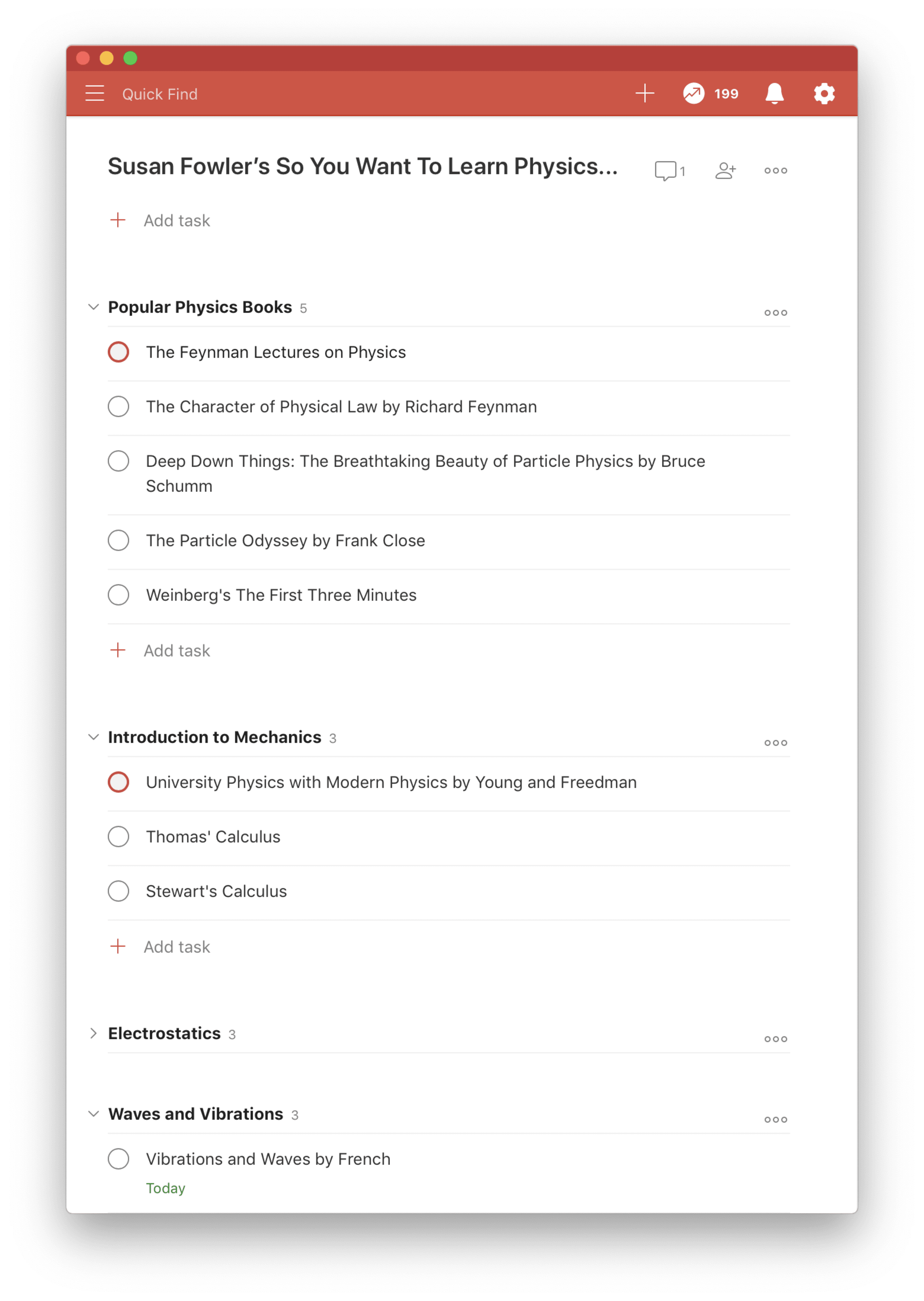

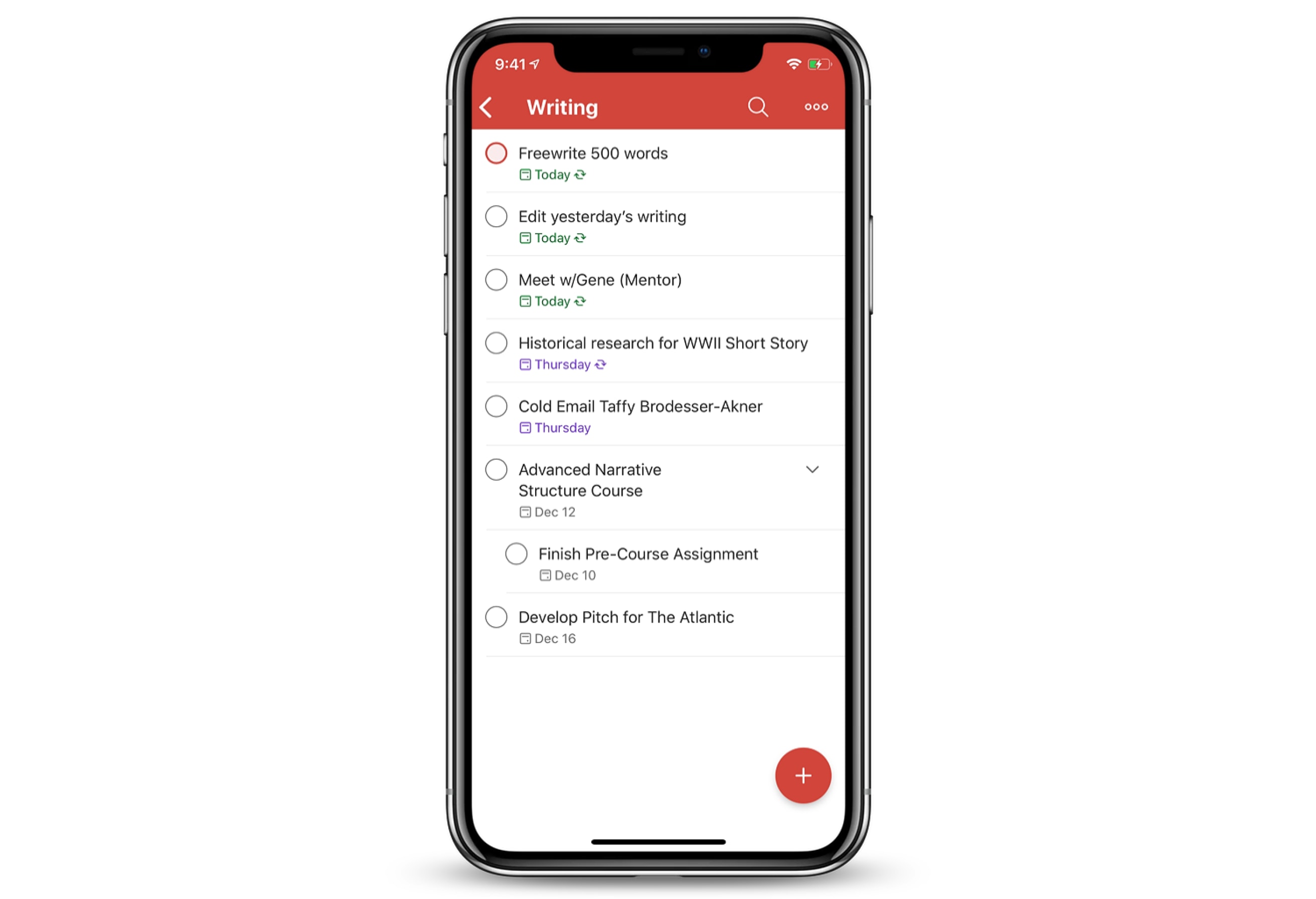

- Have a daily task list that includes your top priorities so you can see them at a glance (e.g. Todoist).

- Use site blockers on your phone and computer when you’re entering periods of deep work and focus (e.g. Self Control, Freedom).

- Say “no” when an opportunity arises that steers us off the path of mastery.

Break Through the Plateau

Mastery is never a straight path. Greene warns against this:

“...you must not see this process of moving through levels of intelligence as merely linear, heading toward some kind of ultimate destination known as mastery.”

Rather than moving in a straight line, you’ll experience a rapid spurt of skill development followed by lulls of stagnation or even regression.

These plateaus can last weeks, months or even years. As we watch peers brush past us and feel our own passion fade away, it can be tempting to give up on our deliberate practice and forgo the path of mastery all together.

Dispel this urge and practice the following instead:

Recognize this phase as part of the journey. The plateau you’re experiencing isn’t unique to you. Rather than seeing stagnation as a result of some personal failing, understand that it’s a natural part of the journey to mastery. The path to excellence is long and arduous. If you’re doing it correctly, you’ll often feel like a beginner over and over again. Leonard provides reassurance that plateaus and normal and expected:

“There’s really no way around it. Learning any new skill involves relatively brief spurts of progress, each of which is followed by a slight decline to a plateau somewhat higher in most cases than that which preceded it.”

By recognizing this phase, you can cultivate patience. Greene describes overcoming this obstacle:

“Real pleasure comes from overcoming challenges, feeling confidence in your abilities, gaining fluency in skills, and experiencing the power this brings. You develop patience. Boredom no longer signals the need for distraction, but rather the need for new challenges to conquer.”

Maintain a 'Beginner’s Mind.' The concept of “Shoshin” or “Beginner’s Mind” originates from Zen Buddhism. It asks people to practice going through life with a sense of openness and to avoid being jaded with expectations and preconceived notions. Or as Steve Jobs put it: "stay hungry, stay foolish".

This mindset is crucial as you naturally meet periods of stagnation in your deliberate practice.

Rather than let plateaus and backslides derail you entirely, take a step back and find ways to recapture the energy and openness you felt when you were just starting out. Waitzkin describes the importance of staying curious while facing challenges:

“When aiming for the top, your path requires an engaged, searching mind. You have to make obstacles spur you to creative new angles in the learning process.”

Here are a few concrete strategies for rediscovering a beginner’s mindset:

- Mentor individuals who are newer to your field, and learn from them.

- Identify your commonly held assumptions, and question their validity.

- Branch out into adjacent fields for inspiration and new perspectives.

- Approach your work without expectations of the result.

- Find opportunities to learn and practice non-competitively.

- Revisit your favorite readings, videos, or discussions from your field.

- Take a break from deliberate practice to come back later renewed.

Over the long stretch of time it requires to reach mastery, coming back to the beginner’s mind will renew your energies.

When we stay the course while experiencing a plateau, we often come back better than before. Waitzkin describes his own plateaus as a chess competitor and how he dealt with them:

“Of course there were plateaus, periods when my results leveled off while I internalized the information necessary for my next growth spurt, but I didn’t mind. I had a burning love for chess and so I pushed through the rocky periods with a can-do attitude.”

Avoid complacency. For some, a plateau brings insecurity and sadness. For others, it brings complacency. “Surely, if I’m no longer progressing, my mastery journey is complete?” This is rarely ever the case. Greene warns against this feeling of complacency:

“The moment that you rest, thinking that you have attained the level you desire, a part of your mind enters a phase of decay. You lose your hard-earned creativity and others begin to sense it. This is a power and intelligence that must be continually renewed or it will die.”

He continues with additional caution to those who have become self-satisfied in their pursuit of mastery:

“This is perhaps the single greatest pitfall of them all. This quality continually haunts you, no matter how disciplined you might think you are. You will convince yourself that your work is essentially over and well done, when really it is your impatience speaking and coloring your judgment. You tend to lose the energy you had when you were younger and hungrier. Unconsciously, you will veer toward repetition — reusing the same ideas and processes as a kind of shortcut.”

By steeling ourselves against the desire to give up when faced with an obstacle, we can come back from plateaus stronger than ever, having learned about the value of patience and resilience.

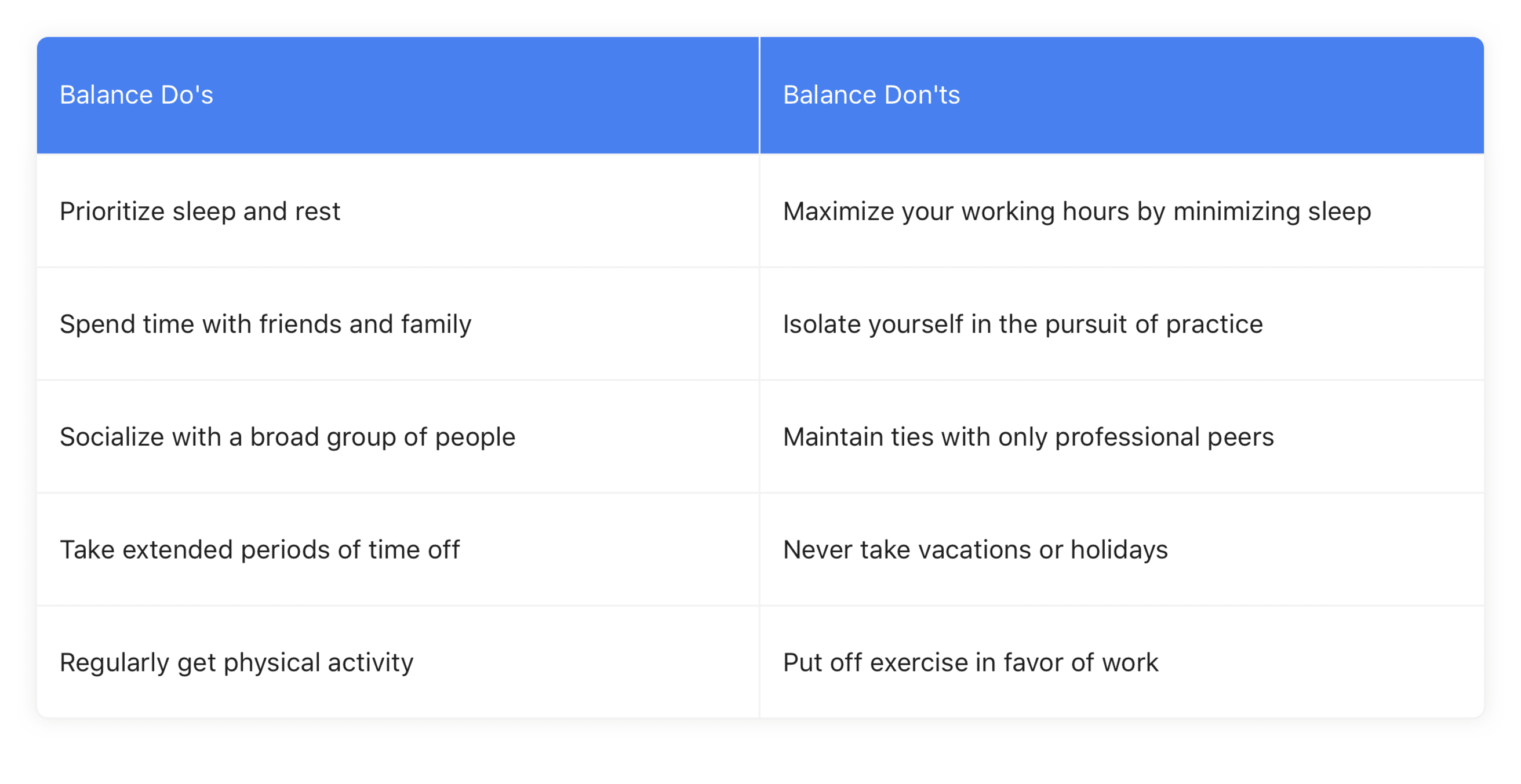

Find Balance

Mastery can be mentally and physically punishing. While your Life’s Task should be a core focus, an unhealthy obsession will inevitably lead to burnout. Waitzkin discusses the importance of interval training, in the form of rest and recovery:

“In your performance training, the first step to mastering the zone is to practice the ebb and flow of stress and recovery. This should involve interval training as I have described above, at whatever level of difficulty is appropriate for the age and physical conditioning of the individual.”

This cycle of rest and recovery doesn’t only apply to physical mastery of a sport or martial art, but anything that requires dedicated long-term focus.

Recovery is an essential tool in your kit that will keep you on the road to mastery for years and decades.

Taking care of yourself ensures you’ll have the endurance to embark on the long road of mastery.

⬆️ Back to the table of contents

Mastery exists in countless fields. We understand this when we pick up a book by Rachel Carson, marvelling at her ability to paint the image of nature in our minds with her command of words. Or when we watch a Martin Scorsese film, astonished by the gritty world he's created on the screen.

This kind of mastery is within our reach too. By staying the path and committing to a lifelong learning expedition, we can capture greatness for ourselves.